Courageous Conversations: Engaging Citizens in Conversations that Matter

The Holocaust launched a human rights revolution in the 20th century as the global community denounced the inhumanity that had occurred. The Holocaust is the clearest example of the destruction and devastation that can result if a civil society abdicates the responsibility to promote, protect, and respect the rights of its citizens. Through this tragedy, citizens the world over discovered what they cared about. The 1948 United Nations Declaration outlined universally guaranteed fundamental human rights. With rights come responsibilities. Nations are made up of citizens and it is those citizens who must now animate a 21st century responsibility revolution.

In order to evoke a successful responsibility revolution, citizens must discover and declare their moral imperatives. This realization occurs when individuals and systems are informed and invited to take responsibility to respond to issues that matter. Citizens around the world face many issues that demand immediate attention and response.

The Concentus Citizenship Education Foundation asked the Saskatchewan Educational Leadership Unit to engage scholars to research and write a 1,500-word précis on: the Holocaust, mental health and addictions, racial discrimination, disability, Indigenous cultures and awareness, and gender. This was no easy task. While these issues are complex, and volumes could be written on each of the six topics, these précis provide an overview and a common starting place for discussion. You may wonder why these issues were chosen and other important issues were not. Consider this the first in a series of courageous conversation documents.

As Canadians, and as global citizens, there are many brave conversations to initiate. These six topics were designated in the hope of making them more visible and accessible for discussion and action. An understanding of, and commitment to, these issues are foundational to citizens developing a full understanding of what it means to be a responsible, respectful, and participatory citizen committed to justice in a pluralistic Canadian democracy. It is my hope that this document will encourage and enable citizens to engage in conversations that matter.

Imagine if citizens worldwide were brave enough to learn about issues that matter, and if they were courageous enough to start conversations on these topics. Why not take the challenge to discuss these issues with people you know? Next, be courageous and talk to people you do not know. Finally, engage those who are typically outside your personal and professional circles. What would you learn? What would you do better? How might these conversations revolutionize your beliefs and values and your relationships with citizens here at home? Further afield, how would your reflections impact those who live around the globe? How can you honour your responsibilities by taking positive action on these issues?

This resource was created to help you facilitate discussions in your home, classroom, business, or organization in order to change our world. We need to engage citizens to become advocates for equality in a free and democratic society. For many citizens, raising their voices on these topics requires great courage, and in some instances, your fellow citizens are still struggling to have their voices heard. Unresolved issues threaten our commitment to a just society. Each of us must become informed and then respond to the call to be a part of this responsibility revolution. As individuals, and as members of small groups, now is our chance to do better.

Thanks to the efforts of these six contributors – and the Saskatchewan Educational Leadership Unit – this document exists as a support for individuals and agencies that are willing to be part of the responsibility revolution. The invitation to have courageous conversations about pertinent topics that matter has been issued. As you explore these and other complex social issues, you are challenged to make a personal commitment to help communities discover what they care deeply about and to find creative solutions to make our world a better place now, and in the future. I believe meaningful conversations will change our world. Let the courageous conversations begin.

David M. Arnot

Chief Commissioner

Saskatchewan Human Rights Commission

The Holocaust and Human Rights

What Do We Mean by the Holocaust?

Holocaust: The Degeneration of Citizenship

A New Framework for Human Rights

Teaching the Holocaust

The Holocaust and the Future

Appendix: Comparative Guidance for Teaching the Holocaust

References

Introduction

What is Mental Health?

A Ten Year Mental Health and Addictions Action Plan for Saskatchewan (2014)

Changing Directions, Changing Lives: The Mental Health Strategy for Canada (2012)

The Mental Health Strategy for Canada: A Youth Perspective (2013)

Informing the Future: Mental Health Indicators for Canada (2015)

First Nations, Inuit and Métis Perspectives and Mental Health

Summary

References

Appendix

Race

Racism in Canada

Racial Discrimination

Failure to Address Racism

Racism Experienced by Indigenous Peoples

Racial Discrimination & Canadian Immigration

Remaining Challenges

References

Introduction

Impact of Disabilities

Medical Model

Social Model

Rights-Based Model

Inclusion

Saskatchewan Context

References

Introduction

The Treaties

The Pass System and Reserve Life

Residential Schools

The 60’s Scoop

Long Term Effects of Colonialism

Conclusion

References

Introduction

Terminology

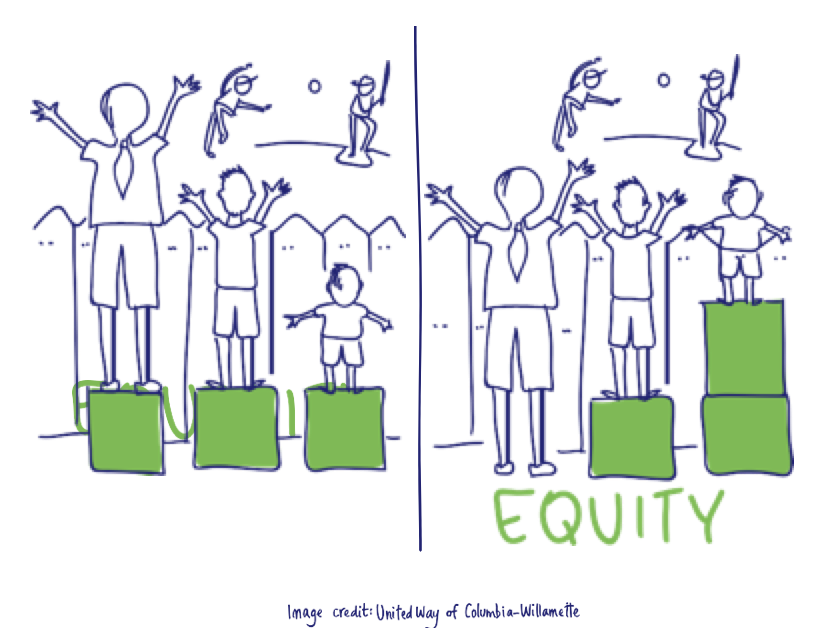

Gender Equality and Gender Equity

Gender as a Human Rights Issue

Intersectionality and Discrimination

Caution: Essentializing and Dichotomizing

Conclusion

References

Masters Student, Institute of Education

University College London

How do you teach events that deny knowledge, experiences that go beyond imagination? How do you tell children, big and small, that society could lose its mind and start murdering its own soul and its own future? How do you unveil horrors without offering at the same time some measure of hope? Hope in what? In whom? In progress, in science and literature and God? (Wiesel, 1978, p. 270)

The Holocaust is humanity’s darkest moment, a ‘negative absolute’ (Desbois, 2008). It is the definitive case study of what can happen when respect for the universality of human rights collapses and shows us “the susceptibility of ordinary people to acts of unspeakable cruelty” (Welker, 1996, p. 102). Learning about the Holocaust gives us the opportunity to explore what lessons we can learn from this dark past (Barton & Levstik, 2004) and to understand the international framework of human rights which it provoked.

Germany’s loss of the First World War (1914-1918) made these problems worse. Jews and communists were frequently blamed for this and other national crises. Public upset at the war was exacerbated by a tumultuous decade ending with the Wall Street Crash and a global Great Depression (Evans, 2003). The Nazis rose to power in the midst of this turmoil and Adolf Hitler became Chancellor in 1933. Hitler’s own correspondence shows that he considered the Jews a threat to Germany and envisioned their de-legitimation and expulsion as early as 1919 (Noakes & Prindham, 1983). Yet Nazi power did not arise primarily on account of anti-Semitism. Instead, the Nazi’s electoral popularity grew from 2.6% in 1928 to 37% in 1932 on account of economic anxiety; by 1932, this anxiety had bred a disenchantment vulnerable to Hitler’s more demagogic leadership (Evans, 2003; Koonz, 2003).

In power, the Nazis sought to methodically remove the civil rights of German Jews and then of other Jews as the Reich subsequently expanded (Michman, 2014). Many attempted to leave or sought to send their children abroad. However, the Depression and anti-immigration sentiment meant most nations, including Canada, were closed to prospective refugees. (Abella & Troper, 1986; Ogilvie & Miller, 2010). In September 1939, the Nazis invaded Poland triggering the Second World War. Poland had the highest population of Jews in Europe resulting in a substantial increase in Jewish killings and mass deportations to ghettos (Browning, 1992).

In June 1941, Germany invaded the Soviet Union specifically deploying Einsatzgruppen, killing squads, to mass murder Jews in Eastern Europe marking the beginning of the Holocaust as a consciously genocidal program (Browning, 1998; Hilberg, 1985; Wachsmann, 2015). The “Wannsee Conference” was then held in January 1942 to coordinate this “Final Solution.” Deportations to purpose-built extermination camps followed and gas chambers were used to murder on an industrial-scale until 1945 (Cesarani, 2016).

The Convention was designed to broaden the international legal framework available to address genocide. Deeply influenced by the Jewish-Polish scholar Raphael Lemkin (Zimmerer & Schaller, 2009), it criminalised “acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial or religious group, as such” (UN, 1948a, Art. II). The Convention was foundational for the later creation of the International Criminal Court and the recent Right to Protect doctrine which emerged following the 1994 Rwandan genocide (Holmes 1998; Kikoler, 2009; UN, 1999).

The Declaration, a non-binding statement drafted by an international committee, sought to establish an international consensus on what rights were universal (Glendon, 1998). It begins by declaring the innate freedom and equality of all persons and the endowment of each of those persons with reason and conscience (UN, 1948b). It then outlines an impressively wide range of inalienable personal, social, and political rights. Today, it is at the very heart of international human rights, both invoked in its own right and as inspiration for a vast range of further declarations and conventions (Kennedy 2006; Lauren, 1998; Roth, 2015; von Bernstorff, 2008).

Students studying the Holocaust should learn about the topic in an age-appropriate way. Care should be taken with explicit images and acting out the roles of victims or perpetrators should be avoided (Schweber, 2004; Wieser, 2001). Materials used should be historically accurate and representative, and should avoid stereotyping, generalisations and simplification (Gray, 2015). Students must be able to recognise the significance of key events that led to the Holocaust (Hammond, 2001), but also study a range of individual stories – including those of rescue and resistance (Kitson, 2001). This balance of a broad understanding and knowledge of specific stories is vital to help students avoid Holocaust distortions, denial, and trivialisation (Gray, 2015). Students should also learn to recognise the ways that authority and advertising shape their own views, in order to develop critical independence (McGuinn, 2000).

History is not stationary; it is the dynamic product of the community who has produced it. Our shared conviction that the Holocaust was deplorable can only continue insofar as we remember and respond to it (Kellner, 1997). Holocaust education will inevitably be an imperfect offering and the democratic challenges of the 21st century may be starkly different to those of the 20th century. But should we find ourselves in circumstances which echo moments along the path that led to the Holocaust, “[n]o longer can we plead ignorance – ‘I didn’t know what was happening’ – as a justification for inaction” (Roth, 2015, p. 17).

explore a variety of victim’s experiences, including resistance; be aware of source limitations, including those on the Internet

Select appropriate learning activities

Abella, I. and Troper, H. (1986). None is too many: Canada and the Jews of Europe, 1933–1948. Toronto, ON: Random House.

Andrew, R. (2005, October). The Canadian holocaust – retrieving our souls. Occupational Therapy Now: 19-20. Retrieved from www.caot.ca/otnow/Sept05/Sept05OTNow_Souls.pdf

Barton, K. C. and Levstik, L. S. (2004). Teaching history for the common good. London, UK: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Bauer, Y. (1978). The Holocaust in historical perspective. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Bloxham, D. (2009). The final solution: A genocide. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Browning, C. R. (1992). The Path to genocide. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Browning, C. R. (1998). Ordinary men: Reserve police battalion 101 and the final solution in Poland. London, UK: Penguin.

Cesarani, D. (2016). Final solution: The fate of the Jews 1933-1949. London, UK: MacMillan.

Desbois, P. (2008). The Holocaust by bullets. New York, NY: Palgrave.

Evans, R. (2003). The coming of the Reich. London, UK: Penguin.

Fontaine, P. & Farber, B. (2013, October 14). What Canada committed against First Nations was genocide; the UN should recognize it. Globe and Mail. Retrieved from www.theglobeandmail.com/opinion/what-canada-committed-against-first-nations-was-genocide-the-un-should-recognize-it/article14853747/

Glendon, M. (1998). Knowing the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Notre Dame Law Review, 73(5), 1153-1190.

Gray, M. (2015). Teaching the Holocaust: Practical approaches for ages 11-18. London, UK: Routledge.

Hansard HC Deb. (December 17, 1942). Vol. 385 col 2082-7 [electronic version]. Retrieved from http://hansard.millbanksystems.com/commons/1942/dec/17/united-nations-declaration

Hammond, K. (2001). From horror to history: Teaching pupils to reflect on significance. Teaching History, 104, 15-23.

Hilberg, R. (1985). The destruction of the European Jews. New York, NY: Holmes & Meier.

Holmes, J. A., Jr. (1998). The International Criminal Court: History, development and status. Santa Clare Law Review, 38(3), 744-836.

Holocaust Educational Trust (n. d.) General principles for teaching the Holocaust. London, UK: Holocaust Educational Trust.

International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance. (n.d.) How to teach about the Holocaust in schools. Retrieved from www.holocaustremembrance.com/node/319

Katz, S. T. (1996). The uniqueness of the Holocaust: The historical dimension. In A. S. Rosenbaum (Ed.), Is the Holocaust unique? Perspectives on comparative genocide (pp. 19-38). Oxford, UK: Westview.

Kellner, H. (1997). “Never again” is now. In K. Jenkins (Ed.), The postmodern history reader (pp. 397-412). London, UK: Routledge.

Kennedy, P. (2006). The parliament of man: The United Nations and the quest for world government. London, UK: Penguin.

Kikoler, K. (2009). Responsibility to protect [conference paper]. Oxford, UK: Refugee Study Centre. Retrieved from www.rsc.ox.ac.uk/files/publications/other/dp-responsibility-to-protect-2009.pdf

Kitson, A. (2001). Challenging stereotypes and avoiding the superficial: A suggested approach to teaching the Holocaust. Teaching History, 104, 41-48.

Koonz, C. (2003). The Nazi conscience. Cambridge, MA: Harvard.

Lauren, P. G. (1998). The evolution of international human rights: Visions seen. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Lecomte, J. M. (2003). Teaching in Europe about the Holocaust and the genocides of the 20th century. In G. Short (Ed.), Teaching about the Holocaust and the history of genocide in the 21st century (pp. 8-13). Strasbourg, France: Council of Europe.

Lewy, G. (1999). Gypsies and Jews under the Nazis. Holocaust and Genocide Studies, 13(3), 64-76.

McGuinn, N. (2000). Teaching the Holocaust through English. In I. Davies (Ed.), Teaching the Holocaust: Educational dimensions, principles and practice. London, UK: Continuum.

Michman, D. (2014) ‘The Holocaust’ – do we agree what we are talking about? Holocaust Studies, 20 (1-2), 117-128.

Morrissette, P. J. (1994). The holocaust of First Nation people: Residual effects on parenting and treatment implications. Contemporary Family Therapy, 16(5), 381-392.

Noakes, J. & Prindham, G. (1983). Nazism: 1919-1945. A documentary reader (Vol. 1). Exeter, UK: Exeter University Press.

Ogilvie, S. A. & Miller, S. (2010). Refuge denied: The St. Louis passengers and the Holocaust. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Overy, R. (2011). Nuremberg: Nazis on trial. BBC History. Retrieved from http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/worldwars/wwtwo/nuremberg_article_01.shtml

Roth, J. K. (2015). The failure of ethics: Confronting the Holocaust, genocide, and other atrocities. Oxford, UK: Oxford Press.

Rothberg, M. (1994). “We were talking Jewish”: Art Spiegelman’s “Maus” as “Holocaust” production. Contemporary Literature, 35(4), 661-687.

Rosenbaum, A. S. (Ed.). (1996). Is the Holocaust unique? Perspectives on comparative genocide. Oxford, UK: Westview.

Russell, L. (2006). Teaching the Holocaust in school history: Teachers or preachers? London, UK: Continuum.

Schweber, S. A. (2004). Making sense of the Holocaust: Lessons from classroom practice. New York, NY: Teachers College.

Short, G. & Reed C. A. (2004). Issues in Holocaust education. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate.

Stradling, R. (2001). Teaching 20th century European history. Strasbourg, France: Council of Europe.

United Nations (UN). (1948a). United Nations Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. Retrieved from https://treaties.un.org/doc/Publication/UNTS/Volume%2078/volume-78-I-1021-English.pdf

United Nations (UN). (1948b). United Nations Declaration of Human Rights. Retrieved from www.un.org/en/universal-declaration-human-rights/

United Nations (UN). (1999). Establishment of an international criminal court: Overview. Retrieved from http://legal.un.org/icc/general/overview.htm

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. (n.d.). Guidelines for teaching about the Holocaust. Retrieved from www.ushmm.org/educators/teaching-about-the-holocaust/general-teaching-guidelines

von Bernstorff, J. (2008). The changing fortunes of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights: Genesis and symbolic dimensions of the turn to rights in international law. The European Journal of International Law, 19(5), 903-924.

Wachsmann, N. (2015). KL: A History of the Nazi concentration camps. New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Welker, R. P. (1996). Searching for the educational imperative in Holocaust curricula. In R. L. Millen, (Ed.), New perspectives on the Holocaust (pp. 99-121). New York: New York University Press.

Wiesel, E. (1978). Then and now: The experience of a teacher. Social Education, 42(4), 266-271.

Wieser, P. (2001). Instructional Issues/strategies in teaching the Holocaust. In S. Totten and S. Feinberg (Eds.), Teaching and studying the Holocaust (pp. 62-80). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Zimmerer, J. & Schaller, D. (Eds.), (2009). The origins of genocide: Raphael Lemkin as a historian of mass violence. London, UK: Routledge.

Associate Professor, Department of Educational Psychology and Special Education

College of Education, University of Saskatchewan

a state of wellbeing in which you can realize your own potential, cope with the normal stresses of life, work productivity, and make a contribution to your community. Good mental health protects us from the stresses of our lives and can even help reduce the risk of developing mental health issues (Mental Health Commission of Canada, 2013b,

p. 4).

While it is distinguished from mental health problems and illnesses, there is recognition that “mental health issues are the result of a complex mix of social, economic, psychological, biological, and genetic factors” (p. 5). These problems can range in severity, duration and resistance to treatment while also presenting with co-morbid physical illnesses. Overlapping symptomatology is the norm with most classifications acknowledging that specific mental disorders are placed on a spectrum that recognizes levels of severity that will impact the onset, development, course, and corresponding treatment options (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5, 2013). Hence informed differential diagnostic processes are essential to ensure corresponding conclusions are accurate and consistent with rigorous professional standards.

1. Promote mental health across the lifespan in homes, schools, and workplaces, and prevent mental illness and suicide wherever possible.

2. Foster recovery and well-being for people of all ages living with mental health problems and illnesses, and uphold their rights.

3. Provide access to the right combination of services, treatments and supports, when and where people need them.

4. Reduce disparities in risk factors and access to mental health services, and strengthen the response to the needs of diverse communities and Northerners.

5. Work with First Nations, Inuit, and Metis to address their mental health needs, acknowledging their distinct circumstances, rights and cultures.

6. Mobilize leadership, improve knowledge, and foster collaborations at all levels.

The goal of this report was to “improve mental health data collection, research, and knowledge exchange across Canada” (p. 3). The report included indicators that covered a range of topics with the intent of “providing information on access and treatment, caregiving, diversity, economic prosperity, housing and homelessness, population wellbeing, recovery, stigma, discrimination, and suicide” (p. 4). The scope of this report is broad, inclusive and sensitive to the unique needs of specific populations and benchmark comparisons are made that can serve as starting points for further study.

Reported indicators were drawn from different sources “including national surveys and administrative databases” (p. 5) employing the following five selection criteria: meaningfulness, validity, feasibility, replicability, and actionability. Members of their information gathering team included leaders in First Nations, Inuit and Métis mental health, experts in school-based mental health promotion, and members of international initiatives for mental health leadership. Together they formulated a collection of indicators that provided a snapshot of mental health related problems in Canada. Their 63 indicators were presented in one of three colours to represent its relative status:

– Green: good performance; indicator moving in a desirable direction

– Yellow: no change, some concern, or uncertain results

– Red: significant concerns/indicator moving in an undesirable direction (p. 5)

The following website takes you to the Indicators Dashboard where you’re able to click on one of 12 focus areas to explore the related indicators:

https://web.archive.org/web/20160518172625/https://www.mentalhealthcommission.ca/English/informing-future-mental-health-indicators-canada

Staggering statistics tend to have a mind-numbing effect where their overwhelming impact may lead to confusion or inaction. However, statistical evidence that speaks to the efficacy of interventions can fuel hope as well as inspiration. It is critical to invest in mental health now in order to prevent the past from repeating itself (Mental Health Commission of Canada, 2013a).

Indigenous people with limited experience in highly complex government organizations often need assistance in developing the organizational literacy to be able to see and deal with tensions between what they may view as right and good and the organizational culture in which they find themselves. (Mental Health Commission of Canada, 2011a, p. 22)

Furthermore, these tensions are exascerbated when views of mental health and mental illness are conceptualized from variant perspectives, e.g., western vs. aboriginal. The former may privilege individual rights and concerns while the latter values collective responsibilities that aims to engage both family and community members.

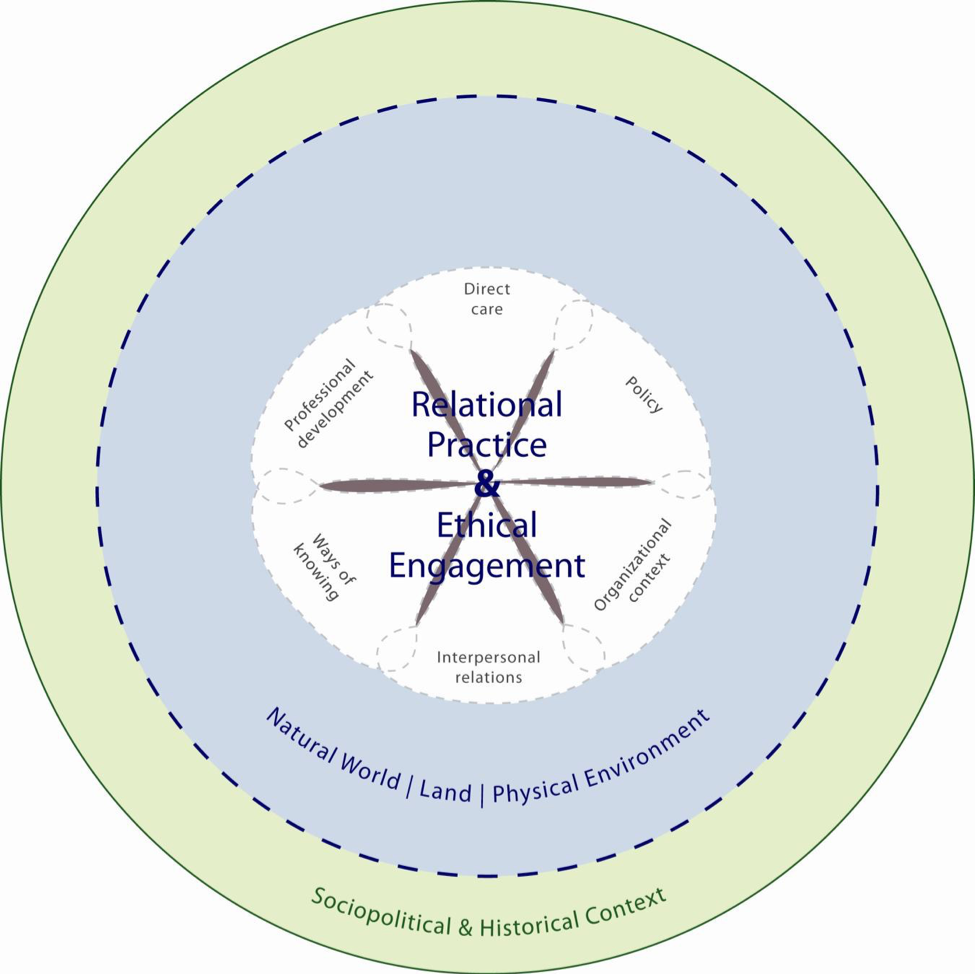

Radical acceptance is promoted as a means of valuing individuality and diversity in an unconditional and non-judgmental manner. If illness is viewed as a “disconnection and imbalance” [then] “healing and recovery is founded on supporting reconnection with self, other, family, community and the natural world” (Canadian Mental Health Commission, 2011a, p. 29).

Healing from trauma-induced illnesses may take many untraditional forms. When the goal is to restore a balance between the heart, spirit, body and mind, a therapist’s office may not be the best or only place for healing and recovery to take place. Alternatives need to be considered and could include land-based healing options where reconnecting with nature may have a parallel internalizing effect on participants that is similar and just as profound. In other words, healing starts from within, and may need periods of silence, reflection and solitude before the inner dialogue can be expressed outwardly. This form of traditional healing is an accepted indigenous practice but may be foreign to many non-indigenous individuals who practice within more traditional forms of western mental health intervention paradigms.

Accessibility is extended beyond physical barriers or adequately trained personnel who are able to deliver culturally informed programming and services to include holistic approaches that consider physical, emotional, mental and spiritual aspects of accessibility (Mental Health Commission of Canada, 2011b). Additionally, a strength-based approach to intervention is encouraged while at the same time being trauma-informed. Acknowledging the effects of intergenerational trauma and its connection to colonial practices is a priority when working with Indigenous peoples.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th Ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

Mental Health Commission of Canada. (2011a). Holding Hope in Our Hearts: Relational Practice and Ethical Engagement in Mental Health and Addictions. Retrieved from:

http://www.mentalhealthcommission.ca/English/system/files/private/document/FNIM_Holding_Hope_In_Our_Hearts_ENG.pdf

Mental Health Commission of Canada. (2011b). “One Focus; Many Perspectives”: A Curriculum for Cultural Safety and Cultural Competence Education. Retrieved from: http://www.mentalhealthcommission.ca/English/system/files/private/document/FNIM_One_Focus_Many_Perspectives_ENG.pdf

Mental Health Commission of Canada. (2012). Changing Directions, Changing Lives: The Mental Health Strategy for Canada, Calgary, AB: Author.

Mental Health Commission of Canada. (2013a). Making the Case for Investing in Mental Health in Canada: 1 in 5 people in Canada lives with a mental illness each year. Retrieved from: http://www.mentalhealthcommission.ca/English/node/5020

Mental Health Commission of Canada. (2013b). The Mental Health Strategy for Canada: A Youth Perspective, Ottawa, ON: Author.

Mental Health Commission of Canada. (2015). Informing the Future: Mental Health Indicators for Canada, Ottawa, ON: Author.

Stockdale Winder, F. (2014). Working Together for Change: A 10 Year Mental Health and Addictions Action Plan for Saskatchewan, Ottawa, ON: Mental Health Commission of Canada.

A holistic view of interrelated forces that enable and constrain relational practice and ethical engagement from First Nations, Inuit and Métis Perspectives¹

Ethical Engagement in Mental Health and Addictions, p. 7.

Department of Educational Administration

College of Education, University of Saskatchewan

Racist beliefs tend to conflate phenotypical attributes with moral character or intelligence, however, biological races have never actually existed (Sussman, 2014). Yet, race and racism are central factors in the social order and racial discrimination based on the social construct of race remains deeply rooted in contemporary society (Battiste, 2013; Schick & St. Denis, 2005b; Sensoy & DiAngelo, 2012). People are racialized through a process known as socialization (Bourdieu & Passeron, 1990; Sensoy & DiAngelo, 2012) which refers to our systematic training into the norms of our culture.

In practice racism represents more than individual acts of discrimination or personal animosity towards groups of racialized people. Coates (2012) emphasized “racism is not merely a simplistic hatred. It is, more often, broad sympathy toward some and broader skepticism toward other” (para. 14). Being persistently followed around while shopping, being denied rental applications by landlords, or being seen as inherently violent without justification are artifacts of racism.

Racial discrimination was initially justified through divinity and endorsed by the Catholic Church. Subsequently race was rationalized by science as evidenced by the infamous eugenics experiments of the 19th century (Stote, 2015). Today, individualism attributes the inequities of racialized groups to individual decisions thus absolving both history and contemporary society from its moral and legal obligations to redress the legacy of racism and colonization. Canada’s dark history was often suppressed or obfuscated from many of its citizens creating challenges for public education and civic discourse geared towards addressing human rights.

Canada is a nation built on the genocide and forced dislocation of Indigenous peoples (Daschuk, 2013; TRC, 2015). For Indigenous peoples, Canada’s racism problem (Macdonald, 2016) continues to represent its largest human rights challenge to date (TRC, 2015). Colonization cultivated the conditions for recurring crisis and standoffs such as Oka, Attawapiskat, Thunder Bay, Elsipogtog, High River, Burnt Church, and Shoal Lake 40. Intergenerational trauma was permitted, with the support of the Crown, by various “civilizing” policies (Battiste & Henderson, 2000) and practices now cited as acts of cultural genocide (TRC, 2015). For example the residential school system forcibly removed children from their families and communities to be placed in religious boarding schools where physical, sexual, emotional, and spiritual abuse were rampant. The 60’s scoop saw children seized by the state and, without permission or knowledge of their parents, placed into care with white families. Forced sterilization (Stote, 2015), medical experiments on unsuspecting Indigenous children (Daschuk, 2013; Mosby, 2013), government sanctioned starvation (Daschuk, 2013), theft of land and resources (AFN, 2013), the infamous Pass System, and abrogation of treaties (Carr-Stewart, 2001) stem from a racist and oppressive system that persecuted Indigenous people for generations.

Racial discrimination is systemic and impacts the well-being of Indigenous people across a variety of domains. The criminal justice system, Child and Family welfare system, and First Nations school systems are pervasively underfunded (APTN National News, 2016; Drummond & Rosenbluth, 2013; TRC, 2015) and systematically marginalized by the government charged with protecting, recognizing, and implementing Indigenous and Human Rights. Indigenous incarceration rates in Saskatchewan are among the highest in Canada with some prisons housing nearly 80% Indigenous people (Arrowmight, 2016) although First Nations represent only 4% of the overall Canadian population (AFN, 2013). Indigenous peoples are also sentenced in Saskatchewan with twice the average jail time as non-Aboriginal people for the same crime (Scott, 2014). There is a disproportionate number of missing and murdered Indigenous peoples (Human Rights Watch, 2013; National Women’s Association Canada, 2015), over-representation in the criminal justice system (RCAP, 1996; Scott, 2014; TRC, 2015), and Indigenous students are more likely to go to prison than graduate from high school (AFN, 2013). Despite the vast array of literature on racism, the impact of racial discrimination ripples across history and contemporary society. The dehumanizing reality of individual and systemic racial discrimination culminates in the tragedies all too common and familiar to Indigenous peoples.

APTN National News. (2016, January 26). Blackstock overjoyed with tribunal win, asks Trudeau to end fight against First Nation children. Retrieved from: http://aptn.ca/news/2016/01/26/blackstock-overjoyed-with-tribunal-win-asks-trudeau-to-end-fight-against-first-nation-children/

Arrowmight. (2016). First Nations justice statistics in Canada. Arrowmight, Canada. Retrieved from http://www.arrowmight.ca/docs/AM-FACT-FN%20Justice%20Stats.pdf

Assembly of First Nations. (2013, October 1-3). Chiefs assembly on education. Gatineau, QC. Retrieved from http://www.afn.ca/uploads/files/events/fact_sheet-ccoe-3.pdf

Battiste, M. (2013). Decolonizing education: Nourishing the learning spirit. Vancouver, University of British Columbia Press.

Battiste, M., & Henderson, S. (2000). Protecting Indigenous knowledge and heritage: A global challenge. Saskatoon, SK: Purich.

Bourdieu, P., & Passeron, J. C. (1990). Reproduction in education, society and culture. London, UK: Sage.

Carr-Stewart, S. (2001). A treaty right to education. Canadian Journal of Education, 26(2), 125-143.

Coates, T. (2012, September). Fear of a black president. The Atlantic. Boston, MA. Retrieved from: http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2012/09/fear-of-a-black-president/309064/

Daschuk, J. W. (2013). Clearing the plains: Disease, politics of starvation, and the loss of Aboriginal life. University of Regina Press.

Drummond. D., & Rosenbluth, E. K. (December, 2013). The debate on First Nations education funding: Mind the gap. School of Policy Studies, Queens University.

Human Rights Watch. (2013, February 13). Those who take us away: Abusive policing and failures in protection of indigenous women and girls in northern British Columbia, Canada. Retrieved from

https://www.hrw.org/report/2013/02/13/those-who-take-us-away/abusive-policing-and-failures-protection-indigenous-women

Jakubowski, L. M. (1997). Immigration and the legalization of racism. Halifax, NS: Fernwood.

Ladson-Billings, G. (1998). Just what is critical race theory and what’s it doing in a nice field like education? International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 11(1), 7-24. DOI: 10.1080/095183998236863

McIntosh, P. (1998). White privilege: Unpacking the invisible knapsack. In P. Rothenberg (Ed.), Race, class, and gender in the United States: An integrated study (pp. 165-169). New York, NY: St. Martin’s Press.

Macdonald, N. (February, 2016). In Canada, justice is not blind. Maclean’s. Retrieved from http://www.macleans.ca/news/canada/cover-preview-in-canada-justice-is-not-blind/

Memmi, A. (2000). Racism. Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press.

Mosby, I. (2013) Administering colonial science: Nutrition research and human biomedical experimentation in Aboriginal communities and residential schools, 1942–1952. Social History. 26(91), 145-172.

National Women’s Association of Canada. (2015). Fact sheet: Missing and murdered Aboriginal women and girls. Retrieved from http://www.nwac.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Fact_Sheet_Missing_and_Murdered_Aboriginal_Women_and_Girls.pdf

Ontario Human Rights Commission. (2016). Retrieved from http://www.ohrc.on.ca/en

Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples. (1996). Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal peoples (Vol. 1–3). Ottawa, ON: Minister of Supply and Service Canada.

Schick, C., & St. Denis, V. (2005a). Critical autobiography in integrative anti-racist pedagogy. In L. C. Biggs, & P. J. Downe (Eds.), Gendered intersections: An introduction to women’s and gender studies (pp.387-392). Halifax, NS: Fernwood.

Schick, C., & St. Denis, V. (2005b). Troubling national discourses in anti-racist curricular planning. Canadian Journal of Education, 28(3), 295-317.

Scott, T. O. (2014, September). Reforming Saskatchewan’s biased sentencing regime. Paper presented to Saskatchewan Legal Aid. Retrieved from

http://www.spmlaw.ca/scdla/JimScott_sentencing_bias_2014.pdf

Sensoy, O. & DiAngelo, R. (2012). Is everyone really equal?: An introduction to key concepts in social justice. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Stote, K. (2015). An act of genocide: Colonialism and the sterilization of Aboriginal women. Halifax, NS: Fernwood.

Sussman, R. W. (2014). The myth of race: The troubling persistence of an unscientific idea. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Trudeau, J. (2016). Komagata Maru apology in the House of Commons. Prime Minister of Canada. Retrieved from http://pm.gc.ca/eng/news/2016/05/18/komagata-maru-apology-house-commons

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2015). What we have learned: Principles of truth and reconciliation. Retrieved from http://www.trc.ca/websites/trcinstitution/File/2015/Findings/Principles_2015_05_31_web_o.pdf

Department of Educational Psychology & Special Education

College of Education, University of Saskatchewan

Although the participation of professionals in diagnosis and recommendations for persons with disabilities will be needed in many cases, the medical model with its focus on the person as the problem and professionals as the sole experts has been largely rejected by persons with disabilities and advocacy groups. In fact, Goodley (1997) argues that the medical model discourages and devalues self-advocacy.

Changing the perceptions that teachers and other people in society have towards persons with disabilities is key to making this approach work. The support that teachers give to inclusion is often connected to the degree to which they focus on the differences and deficits of persons with disabilities in comparison to the importance of social justice in the school context (Lalvani, 2013).

Teachers, parents, and policy makers are often worried that the other children in the classroom will be adversely affected by having a student with a disability fully participating in the classroom. A study comparing students from classrooms with or without a child with disabilities fully included in the classroom were compared in their academic progress over a year. There were no significant differences between the groups (Sermier Dessemontet & Bless, 2013).

The current approach is to differentiate instruction through adaptations (changing how the material is presented) and modifications (changing what is presented) to meet the needs of all students in the classroom (Hutchinson, 2007). Postsecondary institutions are now required by law to make reasonable accommodations to provide equitable access to services for students with disabilities. This change has greatly affected the numbers of students with disabilities accessing and experiencing success in postsecondary studies (Mullins & Preyde, 2013).

In many ways the design was flawed as the assumption that functionality in society can be attained separate from society proved to be false in most cases. As well, society did not appear willing or able to accept the residents after they were trained. Employment opportunities did not materialize and many residents continued to reside at Valley View on a long term basis.

By the end of the 1970s the movement towards community-based programming had begun in earnest and most of the residents of Valley View Centre were moved out of the institution and into group homes or other community-based placements (Wickham, 2012). The Saskatchewan Council for Crippled Children and Adults changed its name to the Saskatchewan Abilities Council in 1984 echoing the societal shift away from the medical model to the social model of disability (Saskatchewan Abilities Council, 2016).

The Saskatchewan Disability Strategy involved community stakeholders in identifying the important direction for transformation in the province. Person-centered services where the organization adapts to the person with a disability, a shift to understanding the impact of the individual with the disability with their participation in the process, accessibility and inclusion benefiting all people, and promoting and protecting human rights were major directions identified by this initiative (The Saskatchewan Disability Strategy, 2015).

References

Brisenden, S. (1986). Independent living and the medical model of disability. Disability, Handicap, and Society (now Disability & Society), 1(2), 173-178.

Gooding, P. (2013). Supported decision-making: A rights-based disability concept and its implications for mental health law. Psychiatry, Psychology, and the Law, 20(3), 431-451.

Goodley, D. (1997). Locating self-advocacy in models of disability: Understanding disability in the support of self-advocates with learning difficulties. Disability & Society, 12 (3), 367-379.

Government of Canada. (1982). The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (Schedule B of the Constitution Act). Retrieved from http://www.publications.gc.ca/Collections/SH37-4-3-2002F.pdf

Government of Saskatchewan. (1979). The Saskatchewan Human Rights Code. Retrieved from http://www.qp.gov.sk.ca/documents/English/Statutes/Statutes/S24-1.pdf

Hutchinson, N.L. (2007). Inclusion of exceptional learners in Canadian schools: A practical handbook for teachers. Second edition. Toronto, ON: Pearson Education Canada.

Hutchison, T. (1995). The classification of disability, Archives of Disease in Childhood, 73(2), 91-94.

Johnston, M. (1994). Models of disability. The Psychologist, 9, 205-210.

Lalvani, P. (2013). Privilege, compromise, or social justice: Teachers’ conceptualizations of inclusive education. Disability & Society, 28(1), 14-27.

Llewellyn, A. & Hogan, K. (2000). The use and abuse of models of disability. Disability & Society, 15(1), 157-165.

Mullins, L. & Preyde, M. (2013). The lived experiences of students with an invisible disability at a Canadian university. Disability & Society, 28(2), 147-160.

Saskatchewan Abilities Council. (2016). About Us. Retrieved from https://www.saskabilities.ca/

Sermier Dessemontet, R. & Bless, G. (2013). The impact of including children with intellectual disability in general education on the academic achievement of their low-, average-, and high-achieving peers. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 38(1), 23-30.

Statistics Canada. (2012). Canadian survey on disability. Retrieved from

http://www.statcan.gc.ca/cgi-bin/IPS/display?cat_num=89-654-X

Stevenson, M. (2010). Flexible and responsive research: Developing rights-based emancipatory disability research methodology in collaboration with young adults with Down Syndrome. Australian Social Work, 63(1), 35-50.

The Saskatchewan Disability Strategy. (2015). People before systems: Transforming the experience of disability in Saskatchewan. Retrieved from http://www.qp.gov.sk.ca/Publications…/People-Before-Systems-Strategy.pdf

Wickham, B. (2012). Valley View Centre Moose Jaw. Report prepared for the Ministry of Parks, Culture, and Sport. Retrieved from http://publications.gov.sk.ca/details.cfm?p=8465

Educational Administration

College of Education, University of Saskatchewan

The culture based on buffalo developed over thousands of years. Homes called tipis were portable and built from materials readily available. FNs transported goods and household possessions by dog and travois. Their clothing was made from tanned animal skin such as buffalo, antelope, elk or deer. Around 1700 the horse was introduced and became an essential part of FNs culture; FNs became skilled riders. FNs beliefs, values, and traditions were from the Creator. Elders passed on oral stories and legends, and children learned creation stories. People depended on nature-given stocks for survival, and they treated the earth respectfully. This was “reflected in songs, dances, festivals and ceremonies” (INAC, 2013, p. 21). Paget (2004) observed the “Plains people are a ‘model’ race” and FN women were the “most attentive mothers” (p. xxi).

The Saskatchewan Government maintained that since Saskatchewan did not exist at that time, it was not a party to the treaties (OTC, 2007). The federal government has legislative authority over Indians and their lands under s. 91(24) of the Constitution Act, 1867. Aboriginal rights, which are separate from Treaty Rights, are the practices, customs, and traditions unique to FNs that FNs participated in prior to contact with Europeans. The “courts have also expanded the scope of…existing Aboriginal and treaty rights” (OTC, 2007, pp. 157 – 158).

By the 1960s, FNs were well groomed. Indian Affairs had a firm grip on band councils who acted as “rubber-stamps for…Indian Affairs” (Dosman, 1972, pp. 22–23). Reserve stratification resulted in “leading families” competing in a “hotbed of politics” where winning earned “respect and privilege” and losing meant “impoverishment and permanent exclusion” (p. 60).

By the 1980s, Indian Affairs had become bloated by bureaucracy. It was a three-tiered system with overlap in responsibilities and programs. Services were delivered as a matter of policy not based on constitutional and treaty obligations (Brezinski, 1993). Flawed priorities, policies, and decision-making resulted from “overlap in jurisdiction” (p. 381).

The child’s formative years were absent of parental influence. Children lived at the school for ten months with only two months at home. They constantly had to adapt and readapt without support. Caldwell (1967) stated children could not “handle this struggle on their own (p. 61). Innes (2013) interviewed an Elder who stated “we never learned about family; [families were] already separated…brainwashed…[and] that took away…our given right to know about our own relatives and family” (p. 108 – 109). She finally understood “it’s not just one…it’s everybody…I understand that now” (p. 109). Paget (1907), almost 60 years earlier, “directly challenged negative representations and distortions of Aboriginal people” used to justify the creation of residential schools (p. xxiii). However, by the 1960s the FN family as an institution was effectively destroyed.

The TRC 2015 emphasized the child-welfare system is the residential school system of our day. Child apprehension continues because of the residential school experience and prejudice toward Aboriginal parents; that is “Aboriginal poverty [is viewed as] neglect” (p. 105).

The Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (RCAP) (1996) found historical false assumptions have continued to influence Canadians. Although not grounded in treaty principles, the Indian Act treats FNs as “inherently inferior and incapable of governing themselves; and that treaties are mere “bureaucratic memorandum of understanding” (p. 229). If Canadians accept that context, then “ward-ship is appropriate…[and government] actions [are]…for [FNs] benefit” (p. 229). FN consent was irrelevant; programs and progress were “defined by non-Aboriginal values alone…[with success]…measured by being civilized and assimilated” (p. 229). Today the standard for FN mainstream acceptance is portrayed as acquiring middle-class values and lifestyles funded by “resource development and resource exploitations” (pp. 229 –230). In a sense, recognizing Aboriginal and Treaty rights threatens those two critical economic interests. New false assumptions have replaced the old. Today, FNs are an “interest group” akin to labour not “entitled to be treated as nations” (p. 232). Change is set against oppressive policy processes entrenched by a “200-year history of [FN] losses” (p. 234).

Abuses of Power

FNs political representation is seen as illegitimate, rather than legitimately emerging out of a treaty relationship. FN geographical population dispersal and complex bureaucracies limit political influence and allow government to “deflect blame and postpone action” (RCAP, 1996, p. 230). Such abuse would not be tolerated in a western democratic nation (p. 230). The Indian Act is a “battering ram…[that] invade[s]…unimpeded…unconscionable; [and]…bureaucrat discretion is punitive…without…public scrutiny” (p. 231). Although the combined effects are “harder…to unravel and change [however],…FNs fear change” (p. 231).

The impact of the residential schools continues to be experienced by the disrupted families and Aboriginal children who continue to be placed in care. Today’s educational system must bear responsibility for arguable gaps in current educational success. Aboriginal health status remains far below national standards because FN children’s health “was undermined by inadequate diets, poor sanitation, overcrowded conditions, and a failure to address the tuberculosis crisis” (TRC, 2015, p. 101). And finally, “punitive discipline…..physical and sexual abuse…have links…to over-incarceration and over-victimization” (p. 101).

Brizinski, P. (1993). Knots in a string: An introduction to Native Studies in Canada. Saskatoon: University Extension Press, Extension Division, University of Saskatchewan.

Caldwell, G. (1967). Indian residential school: A Research study of nine residential schools in Saskatchewan. Ottawa, ON: The Canadian Welfare Council.

Dosman, E. J. (1972). Indians: The urban dilemma. Toronto, ON: McClelland and Stewart.

Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC). (2013), First Nations in Canada, Ottawa, ON: Government of Canada. Retrieved from https://www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca/eng/1307460755710/1307460872523#chp1

Innes, R. A. (2013). Elder brother and the law of the people: Contemporary kinship and Cowessess First Nation. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press.

Lerat, H. (2005). Treaty promises Indian reality: Life on an Indian reserve. Saskatoon, SK: Purich Publishing.

Office of the Treaty Commissioner (OTC). (2007). Treaty implementation: Fulfilling the covenant. Retrieved from http://www.otc.ca/resource/purchase/statement_of_treaty_issues.html

Office of the Treaty Commissioner (OTC). (2016). Treaty information sheets. Retrieved from

http://www.otc.ca/resource/purchase/treaty_timeline.html

Paget, A. (2004). People of the plains. Regina, SK: Canadian Plains Research Center, University of Regina.

Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples. (1996). Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal peoples (Vol. 1 & 2). Ottawa, ON: Minister of Supply and Service Canada.

Satzewich, V. & Mahood, L. (1994). Indian affairs and band governance: Deposing Indian chiefs in western Canada, 1896-1911. Canadian Ethnic Studies, 26(1), 40.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2015). What we have learned: Principles of truth and reconciliation. Retrieved from http://www.trc.ca/websites/trcinstitution/File/2015/Findings/Principles_2015_05_31_web_o.pdf

Associate Dean of Undergraduate Programs, Partnerships and Research

College of Education, University of Saskatchewan

gender analysis helps us understand how women and men experience human rights violations differently as well as the influence of differences such as age, class, religion, culture and location. It highlights and explores hierarchical and unequal relations and roles between and among males and females, the unequal value given to women’s work, and women’s unequal access to power and decision-making as well as property and resources…the impact of different laws, policies and programmes on groups of men and women. (pp. 35-36)

For example, the Canadian government introduced federal legislation Bill C-16 on May 17, 2016, which would enshrine “gender identity” and “gender expression” as human rights protections within the Canadian Human Rights Act and the Criminal Code (CBC, 2016). These changes would ensure that hate speech law include the two terms and make it illegal to discriminate against members of the LGBTQ community who have faced a history of criminalization, violence, psychiatric labeling, and family rights violations. Gender analysis, therefore, does not exclusively focus on an analysis of women’s issues, but rather, focuses on how particular groups of men and women, and not necessarily all men or all women in all circumstances, experience human rights.

For example, Canadian literature supports the view that the intersection of race and gender positions visible minority women as the most disadvantaged group in Canada (Ambwani & Duke, 2007; St. Denis, 2007). This point is underscored by the recent national inquiry on the generational disregard of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (MMIW) in Canada (Government of Canada, 2016). According to this body of research, visible minority women, and Indigenous women in particular, are positioned as deficient and primitive in Canadian society and their plights are attributed to personal failings rather than to the socially constructed scripts, policies and practices that keep them marginalized and that reinforce continued discrimination (Crawford, 2004). As St. Denis (2007) found, “most, if not all Aboriginal people, both men and women, who are living in western societies, are inundated from birth until death with western patriarchy and western forms of misogyny” (p. 44). The effects of intergenerational trauma from residential schools and the Sixties Scoop has had a genocidal effect on First Nations and Métis families, and has caused tremendous upheaval to the social fabric of Indigenous peoples who are living the intersectional realities of race and gender (Truth and Reconciliation Commission, 2015).

References

Ambwani, V., & Dyke, L. (2007). Employment inequities and minority women: The role of wage devaluation. The International Journal of Diversity in Organizations, Communities and Nations, 7(5), 143-152.

American Psychological Association. (2011). The guidelines for psychological practice with lesbian, gay, and bisexual clients. APA Council of Representatives.

Available at http://www.apa.org/pi/lgbt/resources/guidelines.aspx

CBC News. (2015, Nov. 4). “Because it’s 2015”: Trudeau forms Canada’s 1st gender balanced cabinet. Available at http://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/canada-trudeau-liberal-government-cabinet-1.3304590

CBC News. (2016, May 17). Transgender Canadians should “feel free and safe” to be themselves under new Liberal bill. Available at http://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/transgender-bill-trudeau-government-1.3585522

Crawford, C. (2004). African Caribbean women, diaspora and transnationality. Canadian Woman Studies, 23(2), 97-103.

Government of Canada. (2016). National inquiry into missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls. Available at http://www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca/eng/1448633299414/1448633350146

Mohanty, C.T. (2003). Feminism without borders: Decolonizing theory, practicing solidarity. Durham: Duke University Press.

Saskatchewan Human Rights Commission. (2016). Rights, responsibilities and respect: Essential citizenship competencies. Saskatchewan Human Rights Commission. Available at http://www.concentus.ca/pub/TeacherResources/SchoolsAdmins/Essential%20Citizenship%20Competencies.pdf

St. Denis, V. (2007). Feminism is for everybody: Aboriginal women, feminism and diversity. In J. Green (Ed.), Making space for Indigenous women (pp. 33-52). Winnipeg, MB: Fernwood Publishing.

Taylor, C., Peter, T., Campbell, C., Meyer, E., Ristock, J., & Short, D. (2015). The Every Teacher Project on LGBTQ-inclusive education in Canada’s K-12 schools: Final report. Winnipeg, MB: Manitoba Teachers’ Society. Available at http://news-centre.uwinnipeg.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/EveryTeacher_FinalReport_v12.pdf

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2015). Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to action. Winnipeg: Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Available at https://nctr.ca/assets/reports/Calls_to_Action_English2.pdf

United Nations. (2009). Women facing multiple forms of discrimination. Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights. Geneva: United Nations. Available at http://www.un.org/en/durbanreview2009/pdf/InfoNote_07_Women_and_Discrimination_En.pdf

United Nations. (2010). Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW). United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women. Available at https://web.archive.org/web/20170206201434/https://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/cedaw/

United Nations. (2012). Born free and equal: Sexual orientation and gender identity in international human rights law. Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights. New York & Geneva: United Nations. Available at http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Publications/BornFreeAndEqualLowRes.pdf

United Nations. (2014). Women’s rights are human rights. Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights. New York & Geneva: United Nations.

Available at http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Publications/HR-PUB-14-2.pdf

Wallin, D. (2015). Feminist thought and/in Educational Administration: Conceptualizing the issues. In P. Newton & D. Burgess (Eds.), Educational administration and leadership: Theoretical foundations (pp. 81-103). Toronto, ON: Routledge Publishing.

The Concentus Citizenship Education Foundation was established by the Saskatchewan Human Rights Commission in 2012. This organization is committed to the 3 Rs- rights, responsibilities, and respect-of Canadian citizenship and the five Essential Citizenship Competencies (ECCs) that bind together Saskatchewan’s approach to citizenship education. The Essential Citizenship Competencies are outlined in the chart below:

© 2024 Concentus Citizenship Education Foundation Inc. All Rights Reserved.