Curriculum Outcomes

Alignment with Saskatchewan’s Curricula

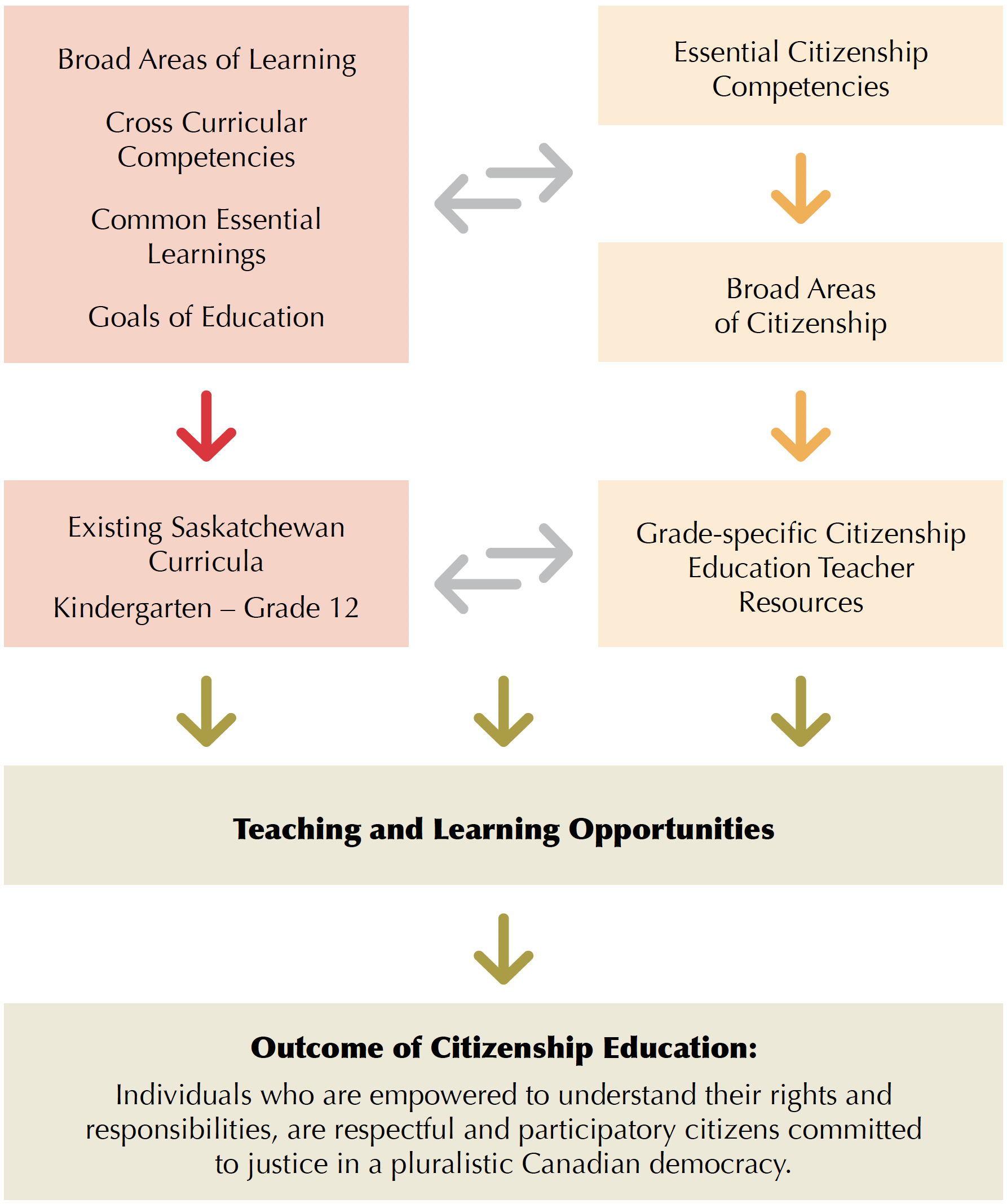

The existing Saskatchewan curricula provide many opportunities to teach citizenship. Those opportunities are enhanced by an explicit, intentional approach to teaching and the strategic addition of teacher resources that assist teachers and students to develop the knowledge, understandings, and dispositions of responsible, respectful, justice-oriented, participatory citizens within the existing curricula. The careful construction of citizenship education in Saskatchewan respects and enhances those approaches existing within the current Saskatchewan curricula. It encompasses the Broad Areas of Learning, Core Curriculum, and Cross-curricular Competencies, which are discussed in the following sections.

Alignment with the Broad Areas of Learning

In determining the basis for building citizenship education, the Saskatchewan Ministry of Education’s Broad Areas of Learning—Sense of Self, Community, and Place; Lifelong Learning; and, Engaged Citizens—were considered foundational. These Broad Areas of Learning refl ect the desired attributes for Saskatchewan’s Kindergarten to Grade 12 students and describe the factual, conceptual, procedural, and metacognitive knowledge that students will achieve throughout their kindergarten to Grade 12 schooling.

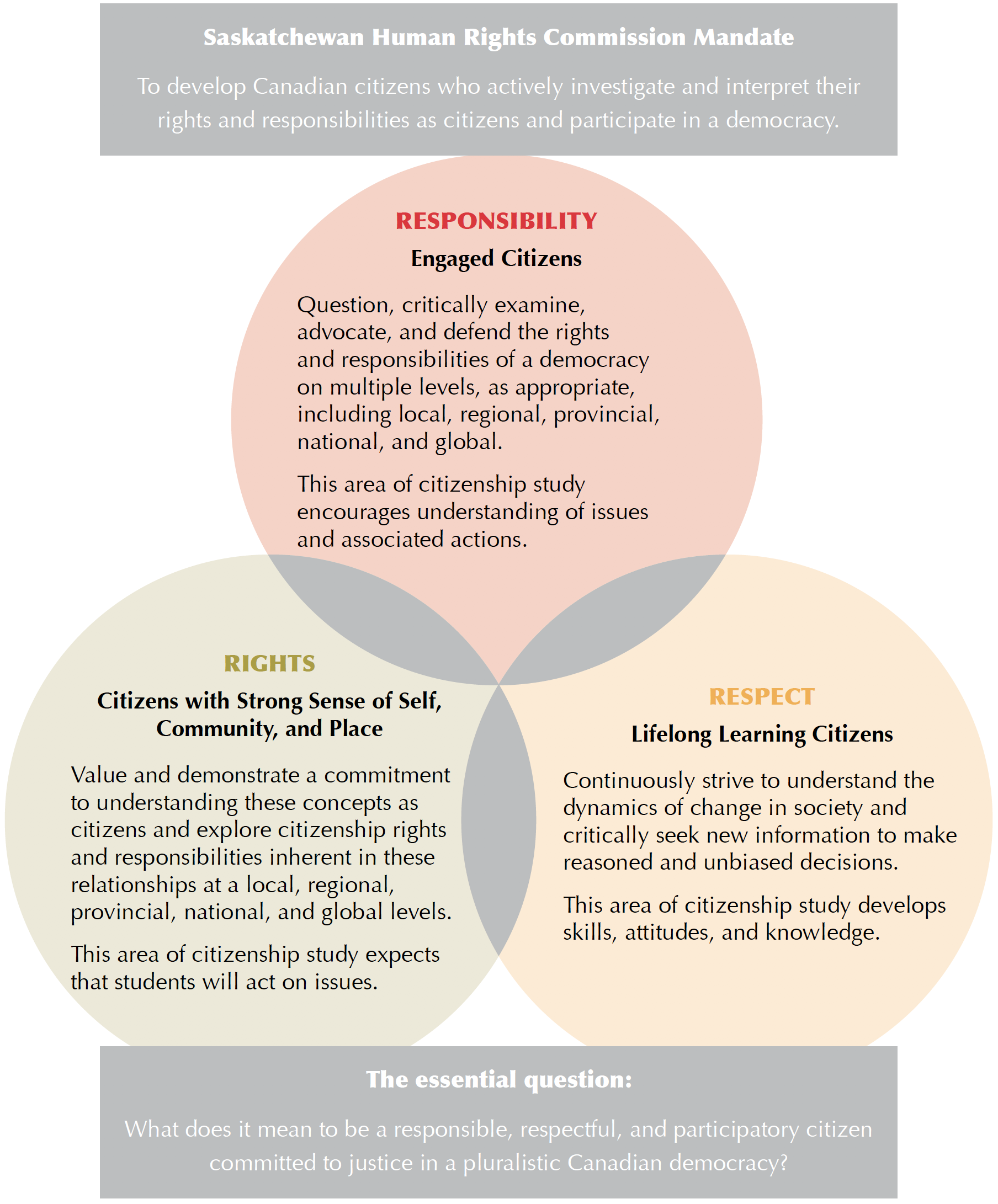

In the development of citizenship education, the Broad Areas of Learning were adapted so each broad citizenship outcome reflected essential citizenship attributes. Named the Broad Areas of Citizenship, these citizenship outcomes not only encompass the essential Ministry of Education outcomes, but also highlight that the citizenship outcomes are not new outcomes; they are existing outcomes made explicit.

The Broad Areas of Citizenship (BACs) form the foundation of citizenship study and reflect the belief that Canadian citizens are engaged citizens who respect the responsibilities of living in a democracy. As lifelong learners, citizens continue to learn about and reflect critically upon the dynamics of change in society, and to value and demonstrate a positive connection to self, community, and place, and the attendant citizenship responsibilities that result from this connection.

Figure 1: The Intersection of the Broad Areas of Citizenship

The BACs are a framework for citizenship learning as well as providing a structure for entry into conversations about citizenship and citizenship participation. The goals defined in the BACs are pervasive and may be addressed through all subject areas explored by students in elementary and secondary schools. The following citizenship goal statements identify what students will learn about citizenship.

• Engaged citizens question, critically examine, advocate, and defend rights and responsibilities embedded in democracy at the local, regional, provincial, national, and global levels.

• Lifelong learning citizens continuously strive to understand the dynamics of change in society, and they critically seek new information to make reasoned and unbiased decisions.

• Citizens with a strong sense of self, community, and place value and demonstrate a positive commitment to understanding these concepts as citizens and to the exploration of citizenship responsibilities inherent in these relationships at local, regional, national, and global levels.

An engaged citizen who, as a lifelong learner, is attuned to current regional or global realities will be able to make informed and unbiased decisions and will understand the responsibilities inherent in specific rights. With a strong sense of self, community, and place, citizens will seek out opportunities to actively participate in their citizenship, work to strengthen their communities, and learn what it means to be Canadian.

Figure 1 provides a schematic to highlight the intersection of the Broad Areas of Citizenship with the mandate of the Saskatchewan Human Rights Commission. The attention to the three R’s—rights, responsibilities, and respect—provides opportunities for students to develop the skills, knowledge, and attitudes to answer the essential question, “What does it mean to be a responsible, respectful, and participatory citizen committed to justice in a pluralistic Canadian democracy?”

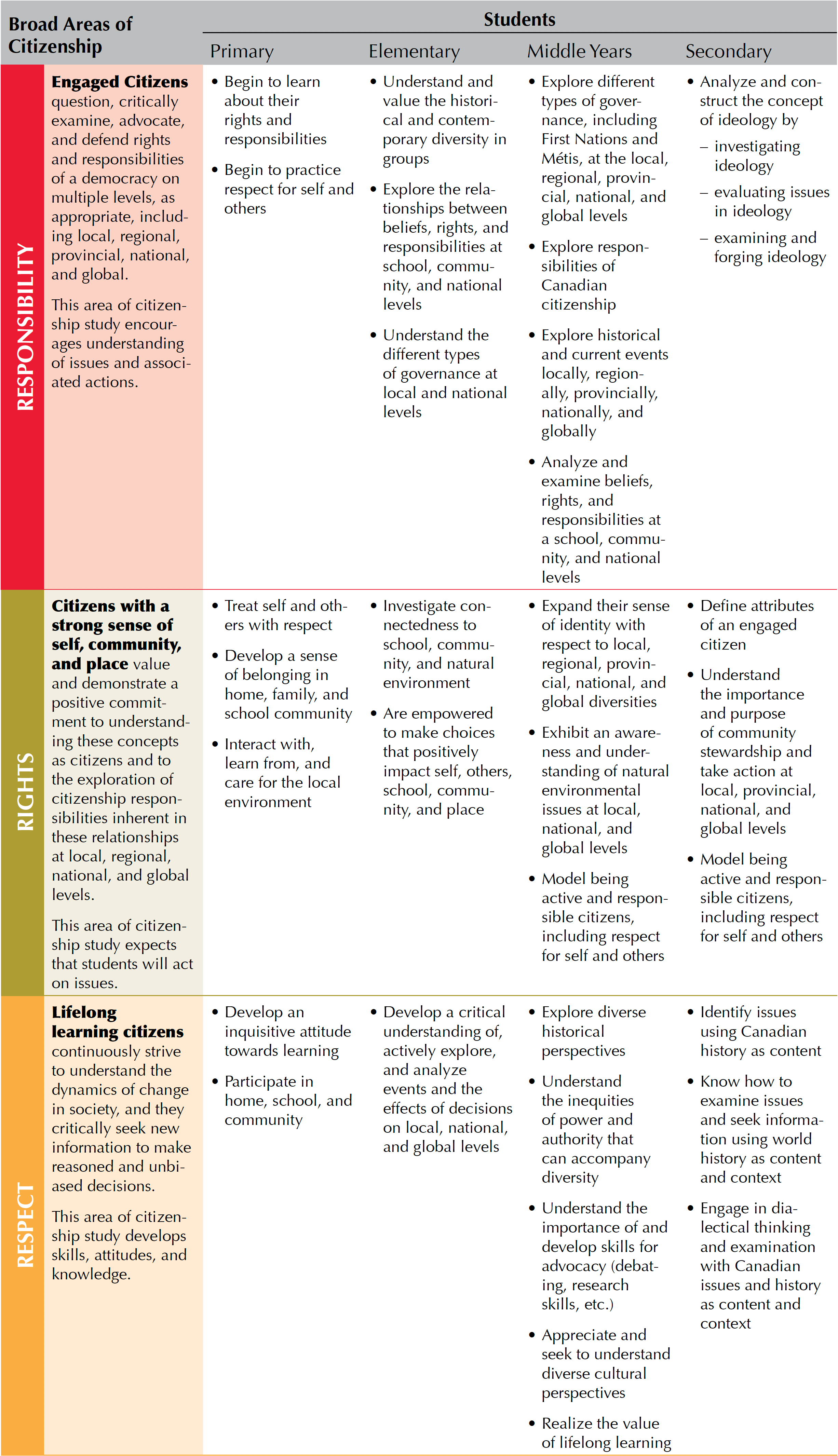

The BACs are further described in a continuum of citizenship education goals and aims for Kindergarten to Grade 12 students in Saskatchewan. The BACs continuum illustrates a shift in locus as students advance through their public schooling. Citizenship issues and participatory opportunities gradually shift from the family and classroom to the community before moving to the region, province, nation, and global contexts. Table 1 articulates the continuum in a condensed “at-a-glance” format.

Table 1: Broad Areas of Citizenship Education at-a-glance

Alignment with Existing Curricula and Cross-curricular Competencies

Saskatchewan curricula are designed as part of the Core Curriculum, which is intended to provide all Saskatchewan students with an education that will serve them well regardless of their choices after leaving school. It reinforces the teaching of basic skills and introduces a range of new knowledge and skills to the curriculum. Core Curriculum is developmental in nature and based on a kindergarten to Grade 12 continuum.

The two major components of Core Curriculum are the Required Areas of Study and the Common Essential Learnings. The Required Areas of Study form the framework of the curriculum. Six categories of Common Essential Learnings are to be incorporated in an appropriate manner into all courses of study offered in Saskatchewan schools.

Saskatchewan curricula are designed to develop four interrelated Crosscurricular Competencies that synthesize and build upon the six Common Essential Learnings. The following competencies contain understandings, values, skills, and processes considered important for learning in all areas of study. These competencies are addressed through all areas of study and through school and classroom routines, relationships, and environments that support creating a linkage into citizenship education program outcomes.

Cross-curricular Competencies:

1. Develop thinking: thinking and learning contextually, creatively, and critically.

2. Develop identity and interdependence: understanding, valuing, and caring about oneself; understanding, valuing, and caring about human diversity, human rights, and responsibilities; understanding and caring about social and environmental interdependence and sustainability.

3. Develop social responsibility: using moral reasoning processes; engaging in communitarian thinking and dialogue; contributing to the well-being of self, others, and the natural world.

4. Develop literacies: constructing knowledge using various literacies; exploring and interpreting the world through various literacies; expressing understanding and communicating meaning using various literacies; literacies include but are not limited to media literacy, information literacy, physical literacy, scientific literacy, and economic literacy. Students should also be developing literacies specific to social studies, including cultural literacy, geographic literacy, and historical literacy.

These components provide the foundation and fi t between citizenship education and existing curricula outcomes. It is imperative that administrators, educators, students, parents, caregivers, and communities acknowledge that learning is not created in a vacuum; children and youth, live and make meaning within their home context and experiences. According to Breithorde and Swiniarski (1999), active citizenship is constructivist and enables students to define problems and issues themselves, create and take action, and then reflect on the impact of their action(s). Regardless of grade level, it is clear that the individual’s experience is central to the construction of knowledge and for this reason needs to be a priority in providing resources for the teaching of citizenship education.

Figure 2 provides a schematic view of the relationship of the existing Saskatchewan curricula and its basic components to the Citizenship Education Program resources. When these are applied to the important teaching and learning opportunities that occur at every grade level, the cumulative outcome should be an empowered individual who understands their rights and responsibilities, and is respectful and participatory as a citizen committed to justice in a pluralistic Canadian democracy.

Figure 2: The Relationship of Citizenship Education to Essential Citizenship Competencies, Broad Areas of Citizenship, Saskatchewan Curricula, and the Citizenship Education Teacher Resources

In Canada, we too have historical experience of government policies which have undermined the rights of minorities and students will necessarily critique their own society when encountering the Holocaust (Lecomte, 2003). The term ‘holocaust’ is now often used analogously in Canada to explain the trauma and abuse experienced by First Nations and Métis people (Andrew, 2005; Fontaine & Farber, 2013; Morrissette, 1994). While these experiences are different than those of the Jews, it is often because of global reaction to the Holocaust that we can now label and challenge these other abuses (Fontaine & Farber, 2013).

History is not stationary; it is the dynamic product of the community who has produced it. Our shared conviction that the Holocaust was deplorable can only continue insofar as we remember and respond to it (Kellner, 1997). Holocaust education will inevitably be an imperfect offering and the democratic challenges of the 21st century may be starkly different to those of the 20th century. But should we find ourselves in circumstances which echo moments along the path that led to the Holocaust, “[n]o longer can we plead ignorance – ‘I didn’t know what was happening’ – as a justification for inaction” (Roth, 2015, p. 17).

Continuum of Study

Grade Correlation to Essential Citizenship Competencies

Enlightened

Historical events have an impact on today’s decisions and today’s understandings impact our perception and interpretation of historical and current events.

Empowered

Governance and public decision-making reflect rights and responsibilities, and promote societal well-being amidst different conceptions of the public good.

Empathetic

Diversity is a strength and should be understood, respected and affirmed.

Ethical

Canadian citizenship is lived, relational and experiential and requires understanding of Aboriginal, treaty and human rights.

Engaged

Each individual has a place in, and a responsibility to contribute to, an ethical civil society; likewise, government has a reciprocal responsibility to each member of society.

These five ECCs bind together Saskatchewan’s approach to citizenship education; the ECCs are neither exclusive of one another nor hierarchical in order or importance. Rather, they intersect, impact, and bolster one other. While this document articulates each one separately, the five ECCs are meant to be considered as an interwoven fabric of citizenship when fully understood.

The teacher resources are organized to provide opportunities for ever-deepening inquiry until the student reaches a core of understanding of the complexities and connections within a particular ECC as well as among ECCs. In this way, a student develops the skills, knowledge, and capacity to be a respectful, responsible, and participatory citizen committed to justice in a pluralistic Canadian democracy. The following sections provide descriptions of the five ECCs and articulate how the teacher resources can build understanding of the complexity encapsulated in each ECC over the continuum of Kindergarten to Grade 12 curricula.

Enlightened

Historical events have an impact on today’s decisions and today’s understandings impact our perception and interpretation of historical and current events.

For as long as history education has been part of the curriculum within Canadian schools, it has been a contentious and controversial subject. There are those who want a cheerleading version of national pride and those who want the “warts and all” version. Some want an exclusive Canadian version, and some want Canada set within a global context. There are those who think history should focus on knowledge and those who think it is about developing skills.

An assumption that there was a golden age when history was taught properly in schools and that a serious decline has occurred is largely a myth. History is about ourselves, about who we are, and about how we define ourselves as a nation, in ways that most other subjects are not. While many subjects are much the same wherever they are taught, historical events taught in England, Japan, or Canada can appear very different.

“Students are expected not only to know what historians know, but also how historians know.”

– Alan Sears

The current approach to history education moves beyond knowing historical information to focus on historical thinking and historical consciousness. The Historical Thinking Project (n.d.) “developed a framework of six historical thinking concepts to provide a way of communicating complex ideas to a broad and varied audience.” The emphasis is on “developing student competencies with the key disciplinary processes of historical work—students are expected not only to know what historians know, but also how historians know” (Sears, 2014).

Historical consciousness studies how people look at the past. For example, history students study John A. Macdonald as a “founding father,” whereas students with historical consciousness consider what he does—or does not—mean as a “founding father” from their standpoints in a multicultural, globalizing, regionalized, gender-conscious 21st century” (Centre for the Study of Historical Consciousness, n.d.).

Citizenship education is set apart from history in several additional ways. The field of citizenship education draws on the knowledge and processes of several disciplines, such as political science, history, sociology, and social psychology.

The ideas and concepts do not have inherent meanings apart from those created and negotiated by people in particular contexts; ideas are fluid and complex and mean different things to different people. For example, while there is agreement that in democracies citizens have a right to participate in their own governance, exactly who gets included is contested—and has been throughout history. Another contentious issue is how citizens give their consent; it is done in various ways in differing types of democratic governance.

There is a role for citizenship education to foster broader conversations about the role and value of including more diverse stories and experiences in national histories. For example, despite rights legislation, many individuals experience their citizenship inequitably. Contemporary examples include citizens who experience inequity because of gender, culture, social class, religion, sexuality, or ethnicity. Citizenship education must acknowledge and consider the impact of those privileges that enhance the ability of some to participate more fully as citizens.

As students research historical events, they seek to understand whose story has been included and whose has been omitted or cleansed from records.

As students research historical events to consider their impact at that time, they also seek to understand whose story has been included and whose has been omitted or cleansed from records. Stanley (1998) writes about the manner in which historical narratives “effect racialisation by creating categories of people whose histories count and others whose histories do not, those who have a history and those who are alleged not to, those who can tell their own history and those who have what is alleged to be their history told for them.”

To develop this competency, students will consider historical events in light of their impact on the present and into the future, and will explore cause and consequence, negative and positive impacts, intended and unintended consequences of policies, events, and decisions. There needs to be discussion of the way history can be “rewritten” by critically reviewing the evidence, motivations, and decision-making processes surrounding a historical event using skills and sensitivities to note the issues of privilege, dominance, and power structures. “Unchallenged, nationalist historical narratives create a binary in term of possible (read acceptable) identities. One can either belong to a place . . . or one is ‘from’ somewhere else. Once is either included by the narrative or one is inexorably excluded. Binaries become the stuff of racialisations, their silences

the stuff of exclusion”(Stanley, 1998).

Students will develop understanding of the diversity and uniqueness of people and that people have different perspectives and points of view. Those points of view are developed by one’s previous experiences, cultural and family traditions, socio-economic status, and beliefs.

Pedagogies that invite students to consider multiple perspectives through a broad range of research, activities, and discussion help students understand and value the historical and contemporary diversity in groups and explore the relationships among beliefs, rights, and responsibilities at local, regional, national, and global levels. The development of skills, knowledge, and dispositions within a personal framework to observe, critique, and respond to current events at these levels is based on understanding the relationships between historical events, present situations, and future aspirations.

Tupper (2009) writes: “While teaching is an ongoing process of curricular negotiation, if teachers are not engaging in a critique of the curriculum they are mandated to teach, but simply making choices about how to deliver content, realize objectives, and evaluate students, the reproduction of particular knowledge traditions remains.”

At the exit to the Canadian War Museum in Ottawa, which is dedicated to a critical history of war, nationhood and national allegiances, the following inscription is displayed:

History is yours to make. It is not owned or written by someone else for you to learn….History is not just the story you read. It is the one you write. It is the one you remember or denounce or relate to others. It is not predetermined. Every action, every decision, however small, is relevant to its course. History is filled with horror and replete with hope. You shape the balance.

This frame for history invites the teacher to partner with the student. Together they use critical pedagogy to investigate the curriculum and shift from the traditional teaching of history to developing deeper understandings that advance the principles of democracy.

Empowered

Governance and public decision-making reflect rights and responsibilities, and promote societal well-being amidst different conceptions of the public good.

Human welfare is defined not only in terms of freedom from hunger and poverty but also in terms of respect for individual dignity. Long-term, sustainable development is closely linked to sound democratic governance and the protection of human rights. Democracy, human rights, and governance cannot be viewed in isolation; they are a critical framework in which all aspects of development must advance.

Democracy, human rights, and governance cannot be viewed in isolation; they are a critical framework in which all aspects of development must advance.

Democracy can be described as an institutional arrangement for arriving at political decisions in which individuals acquire power to decide by means of a competitive struggle for the people’s votes. Democracy is often described as having key political institutions—elected officials, free and fair elections, inclusive suffrage, the right to run for office, freedom of expression, plurality of information sources, and associational autonomy.

There are significant challenges involved in engaging the citizenry in current models of democratic decision-making. Citizens have different conceptions of the “public good” and who benefits most from policy decisions. There is substantial discourse regarding voting, particularly around the scepticism of young people regarding the voting process, and the general beliefs that politicians are untrustworthy and self-interested, that the important issues of human rights and family policy are ignored, and that politicians are unable to deal with the world’s economic forces.

Political disengagement reflects broader changes in political culture, that constellation of ingrained attitudes and dispositions that individuals bring to their understanding of democracy and their own role, and responsibilities within the democratic system (Howe, 2010).

Howe (2010) discusses two facets of disengagement: political attentiveness and social integration. Political attentiveness encompasses trends in political interest, political knowledge, and habits of news media use; social integration is the connections to community and the social norms that influence how people conduct their lives on a general plane and the extent and manner of their engagement with the political world. He posits a significant gap between younger and older citizens on various measures of political attentiveness. Howe notes that “the postwar period has seen significant changes in lifestyles and social norms that have, according to various theorists, gradually weakened the bonds of social integration in the developed democracies” (Howe, 2010). Community in some form or other precedes democracy; a healthy measure of social solidarity and shared public purpose is necessary for democracy to flourish.

Democracy is an open-ended proposition; the goalposts are subject to repositioning as the expectations, ambitions, and capacities of the “the people” evolve.

Democracy is an open-ended proposition; the goalposts are subject to repositioning as the expectations, ambitions, and capacities of the “the people” evolve. The progression of the vote is evidenced by the democratic and free vote granted initially to a minority of the affluent male population opening to include women in 1918 and First Nations populations in 1960, and removing racial and religious discrimination for the 1963 vote. There remain issues of inclusion/exclusion that should continue to force Canadians to examine issues within the institutions and processes of democratic government.

What would a stronger democracy look like. A more vibrant democracy would be one in which there is a stronger sense of common purpose and solidarity among citizens, who manifest their solidarity in part by closely attending to, and regularly participating in, the political life and civil society of the community and country.

Giddens (2000) calls for “democratising democracy” or deepening democracy because the old mechanisms of government do not work in an information-rich society. Democratizing democracy is described as having an effective devolution of power, constitutional reform, and greater transparency in political affairs. Giddens uses the analogy of a three-legged stool—government, the economy, and civil society—needing to be in balance for a well-functioning democracy.

Using citizenship education as a lens, the students are engaged to understand that rules, regulations, policies, and laws are the primary means by which society organizes and brings structure and governance to itself. Students consider the relationship between rights and responsibilities, examine the effects of decision-making processes, and begin to appreciate the responsibilities of governing bodies that develop rules, policies, and structures. Students develop consciousness of the responsibility to contribute to varying levels of governance and the need to critically examine governance structures to understand underlying assumptions and associated implications.

Students research the various levels of government, their responsibilities and their decision-making processes. Students critically examine the varying impacts that decisions have on people, the underlying purposes and assumptions behind these decisions, and who benefits or loses by their application. They examine the processes by which citizens can question, critique, and leverage change within a variety of governmental structures and practices. As students strive to understand issues from a variety of viewpoints, they also explore dispute resolution processes, examine and practice actions that contribute to peace and order, as well as understand those that threaten democratic processes, and they engage critically with their own positions within society.

Empathetic

Diversity is strength and should be understood, respected, and affirmed.

Many people use the terms diversity and multiculturalism interchangeably, when in fact, there are major differences between the two. Diversity is defi ned as the differences between people such as race, gender, sexual orientation, religion, background, socioeconomic status, and much more. Multiculturalism refers to the historical evolution of cultural diversity within a jurisdiction; in Canada, it embodies the institutionalization of cultural diversity.

Multiculturalism ensures that all citizens can keep their identities, can take pride in their heritage, and can have a sense of belonging.

In 1971, Canada adopted multiculturalism as an official policy. In doing so, Canada affirmed the value and dignity of all Canadian citizens regardless of their racial or ethnic origins, their language, or their religious affiliation. The 1971 Multiculturalism Policy of Canada also confirmed the rights of Aboriginal peoples and the status of Canada’s two official languages.

Canadian multiculturalism is fundamental to our belief that all citizens are equal. Multiculturalism ensures that all citizens can keep their identities, can take pride in their heritage, and can have a sense of belonging. The resulting diversity of race, cultural heritage, ethnicity, religion, ancestry, and place of origin allows Canadians to speak many languages, understand many cultures, and participate globally. Critical examination of multiculturalism includes looking at the advantages based on race, gender, sexual orientation and social class that occur as “invisible privileges.” Clearly this examination is about examining our own stereotypes and systems of advantage so we can be more inclusive to a variety of perspectives.

Canadian diversity is a national asset. Canadian citizenship gives us both rights and responsibilities. One of these is to protect those policies and structures that affirm and strengthen Canada’s democracy, ensuring that a multicultural, integrated and inclusive citizenship will be every Canadian’s inheritance. Each citizen must be aware of the complexity and the importance of balancing regional and cultural diversity with maintaining national unity and pride.

As immigration and migration increase, diversity among neighbourhoods and within neighbourhoods increases the likelihood of culturally, racially, and ethnically diverse individuals living next door to each other. Good citizenship education with skilful teacher moderation can provide the safe ground for diverse young people to learn from one another, foster respect for all citizens and imagine a different future for oppressed people.

As immigration and migration increase, diversity among neighbourhoods and within neighbourhoods increases the likelihood of culturally, racially, and ethnically diverse individuals living next door to each other.

In developing citizenship education pedagogy, the mountain of content that might be included fills binders. Levine (2012) suggests that, rather than argue over what to put in or leave out, use relevance to civil society as the main criterion of inclusion: “Diverse people will then bring different and complementary knowledge to bear in a thriving civil society.” He elaborates that not all people need to know each topic as long as some people do—and the venues for discussion and collective action function well. The chief purpose of civics education is to prepare people to strengthen those venues.

In this ECC, teachers engage students in activities that develop student understandings of diversity and the uniqueness of individuals. Students will be given the opportunity to understand that people may have different points of view about the same subject and may come to different conclusions on how to act. Those points of view are developed by previous experiences, cultural and family traditions, and beliefs. The far-reaching effects of diversity expand from the individual to the community and beyond.

Because Saskatchewan is a province populated by Aboriginal peoples, into which settlers moved from other countries and other parts of Canada, students must examine the different groups of people who contributed to the makeup of the province, and the colonial notion of citizenship. They will understand that Aboriginal peoples lived in Saskatchewan prior to immigration and had their own cultures, economies, and forms of governance. In this ECC the students would seek knowledge and understanding of those relationships and the continued implications for all Saskatchewan people.

Canada is a country that purports to celebrate diversity and states that the cultural mosaic serves to enrich our country. Unfortunately, Canadians have not always lived up to that ideal. Students will examine perspectives on Canada’s political evolutions that lead to the development of the country and the formation of provinces and territories; they will critically examine Europe’s influence on pre-Confederation society and the impact of post-colonialism on citizenship. Students will be engaged to develop understanding of the pervasive nature of racism and white supremacy that have been, and continue to be, exhibited within Canada and the world.

Knowledge of the diverse geographic features, specific resources, population clusters, and economic relationships will help students draw understandings about possible causes of today’s issues and consider solutions. Students will appreciate the diversity among countries and cultures, explore cultural perspectives, and cultivate compassion and empathy.

Ethical

Canadian citizenship is lived, relational, and experiential and requires understanding of Aboriginal, treaty, and human rights.

Citizenship is understood and experienced in different ways by people. Key questions need to be posed as Canadians work toward a more democratic society —questions that critically reflect on the different ways in which people live and experience their citizenship. What does it mean to be a “good” citizen? How does life experience impact our understanding of citizenship, our rights and our responsibilities as citizens? How does privilege intersect with citizenship? And why do some people participate in civic activities while others do not?

Students will appreciate the diversity among countries and cultures, explore cultural perspectives, and cultivate compassion and empathy.

A significant conundrum is the definition of a “good citizen” which is often equated to some degree with helping others—particularly those less fortunate, poor, and needy. Tupper et al. (2010) point out that this marker of good citizenship locates the good citizen “implicitly within a middle-class norm” and excludes those located within the grouping of “poor and needy.” For these students, “the knowledge of what constitutes good citizenship is in tension with the way their lived experiences enable them to imagine themselves as citizens.”

In this democracy espousing universal rights and responsibilities, there continue to be significant differences in the lived experiences of its citizens. Cases of differential treatment by law enforcement officials, access to safe and clean drinking water, and the level of priority and resources assigned to finding missing women or their killers are pointed examples of how some citizens are “second class” (Tupper, 2009). It is clear that we need to teach about why some people participate and others do not and that it is not simply a matter of choice. Students need to critically examine the social systems that operate to privilege some individuals over others and the resulting inequities that occur in benefit and participation.

There continue to be significant differences in the lived experiences of one’s citizenship.

Levine (2012) and others assert that to learn active citizenship, one must experience active citizens. Pedagogy that provides authentic experiences in which students address real-world problems that apply to their lives is a powerful motivator and will increase the likelihood of students engaging in civic and political activities throughout their lives. There are indications of significant alternative engagement of young people in grassroots movements (Idle No More), humanitarian projects (Habitat for Humanity, Red Cross), environmental organizations, and extracurricular activities as ways to express their citizenship. Vézina and Crompton (2012) reported that the overall rate of volunteerism is growing in Canada and includes high rates of young adult participation (ages 15-24), particularly in Saskatchewan. The data corroborates that people who were involved in community activities in their childhood or adolescence have a greater tendency to become adults who are involved in civic activities. (Vézina, M. & Crompton, 2012). This reinforces that creating experiential learning will contribute to youths remaining engaged into adulthood. The partnership between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people in Canada has been an integral and important part of Canadian history, and this partnership has implications for the ways that Canadians view themselves as citizens of Canada. Donald (2009) suggests that a curricular and pedagogical challenge of decolonization is to contest the assumption that the historical experiences and perspectives of Aboriginal peoples are their own separate cultural preoccupation. The implication is that colonization is a shared condition, and education should seek ethical relationality as a curricular and pedagogical standpoint. Donald states:

Ethical relationality is an ecological understanding of human relationality that does not deny difference, but rather seeks to more deeply understand how our different histories and experiences position us in relation to each other. This form of relationality is ethical because it does not overlook or invisibilize the particular historical, cultural, and social contexts from which a particular person understands and experiences living in the world. It puts these considerations at the forefront of engagements across frontiers of difference.

“it is unethical for students to live as treaty people without doing the diffi cult and often uncomfortable work of coming to understand the signifi cance of being a treaty person.”

– Jennifer Tupper

Understanding the treaty relationship requires all students to consider how their own lives and privileges are connected to and may be traced through, treaties and the treaty relationship. Tupper (2012) believes “it is unethical for students to live as treaty people without doing the diffi cult and often uncomfortable work of coming to understand the significance of being a treaty person.” She continues, “treaty education has the potential to help all students learn from and through events and experiences of the past in ways that inform not only their historical consciousness, but their dispositions as Canadian citizens, and their relationships with one another.”

Donald (2009) suggests that the focus needs to be on the colonial experience that demonstrates that Aboriginal peoples and Canadians have significant historical relationships that continue to manifest themselves in ambiguous ways to the present day. He continues that this recognition is necessary to counteract the systemic ways in which Indigenous knowledge systems, values, and historical perspectives have been written out of the “official” version of the building of the Canadian nation.

While Tupper’s and Donald’s discussion is specific to treaty, it is applicable to Métis, Inuit, and all those whose stories and experiences have not been included in the mainstream history of the nation. “. . . Attention to the intersections of race, culture, class, gender, religion and sexual orientation as they inform an individual’s ability or inability to engage as a citizen must be present . . . if students are to come away with deeper understandings of the complexities of citizenship and of their own lived experiences as citizens” (Tupper, 2009). The challenge for teachers is to provide the conditions, experiences, and spaces where individual students can develop those complex understandings.

Engaged

Each individual has a place in, and a responsibility to contribute to, an ethical civil society; likewise, government has a reciprocal responsibility to each member of society.

The beginning phrase, “every individual has a place in . . .” reaffirms the strength that comes from the diversity among Canadian citizens as outlined in the previous ECC. This competency then focuses on the contributions required of citizens as they exercise their citizenship. This involves understanding that a key role of a citizen within a democracy is to participate in public life—in both political and civil spheres. Citizens have a responsibility to become informed about public issues, to watch carefully how their political leaders and representatives use their powers, and to express their own opinions and beliefs. Voting in elections is an important civic duty; but to vote wisely, each citizen should listen to the views of the different parties and candidates, and then make his or her own decision on whom to support. Efforts must be made to educate people about their democratic rights and responsibilities, to improve their political skills, to represent their common interests, and to involve people in political life. In a healthy democracy, people engage in questioning, debating and sometimes disagreeing with government.

Every citizen should know and understand their own rights so they do not knowingly transgress the rights of others; and, every citizen has a responsibility to make the world a better place.

Another vital form of participation comes through active membership in “civil society”—that aggregate of independent, non-governmental organizations intended to manifest the interests and will of citizens. Volunteering is often considered a defining characteristic of what constitutes a civil society. In a democracy, every citizen has certain basic rights that cannot be taken away. Everyone has these rights and is under an obligation to exercise the rights peacefully, with respect for the law and for the rights of others. In this vein, the Commission espouses two fundamental responsibilities: Every citizen should know and understand their own rights so they do not knowingly transgress the rights of others; and, every citizen has a responsibility to make the world a better place. Chief Commissioner of the Saskatchewan Human Rights Commission, Judge David Arnot, stated in a speech (2014) to the Saskatchewan Council on Social Sciences:

Our grade 12 graduates will be called upon, and are being called upon, to uphold our democracy. What we need right now, and for our future success, are engaged citizens—citizens who question, critically examine, advocate, respect others, and defend responsibilities and democratic rights at local, provincial, national, and global levels.

This ECC engages students in the consideration of their membership within multiple communities, which affords certain rights, and it also reinforces that there are certain responsibilities to protect those rights and privileges. A person’s “sense of place” develops through experience and with knowledge of the history, geography, and geology of an area, the legends of a place, and a sense of the land and its history. Developing a sense of place helps students identify with their region and with others who inhabit the region. A strong sense of place leads to more sensitive stewardship of both the cultural heritage and the natural environment and includes seeking solutions to issues that occur in their own regions and communities.

When people know more, they do more, and so it follows that citizenship education needs to engage students in active participation in democracy, to critically consider and respond to barriers to such participation.

Students study citizenship issues and challenges within an ever-increasing sphere of influence, beginning with self, others, and their environment. Students at a primary level will practice respect for self, model respect for others, and advocate for the good of others.

Citizenship education resources reflect the belief that when people know more, they do more, and so it follows that citizenship education needs to engage students in active participation in democracy, to critically consider and respond to barriers to such participation. The resources encourage students to move learning about citizenship from their classrooms into active participation in citizenship activities in their families, schools, communities, and beyond. Such active participation is described as community stewardship.

Stewardship is supported through active participation and critical engagement on issues of importance. As students appreciate the reliance of humans on community and the environment, and understand their responsibility to care for their surroundings and society, they develop the concept of community stewardship. Students explore processes for initiating and guiding change in their community with respect to environmental, social, and economic issues. They learn how various community groups influence decisions and consider the ways they can hold governments, businesses, organizations, and elected officials accountable. When students actively contribute their time to participate or initiate, design, and organize community stewardship initiatives that protect or enhance the environment and community, they are demonstrating the depth of understanding desired as an outcome.

This ECC invites students to develop a critical framework in which to delve below the symptoms of issues to get to root causes, consider alternate solutions and their potential impacts in order to determine actions to create positive change. These critical thinking skills and processes linked to action will entice students toward becoming more justice-oriented citizens.

In summary, these five essential citizenship competencies frame the skills, knowledge and dispositions deemed necessary for an individual to participate fully as a respectful, responsible citizen. Over the course of a student’s Kindergarten to Grade 12 experiences, the interwoven fabric of these ECCs will support the student’s development into an enlightened, engaged, empathetic, ethical, and empowered citizen.

© 2024 Concentus Citizenship Education Foundation Inc. All Rights Reserved.